India has a federal form of governance. Success of food and nutrition security measures call for negotiations vitally required between the Centre and the States pertaining to them, writes K.R. Venugopal.

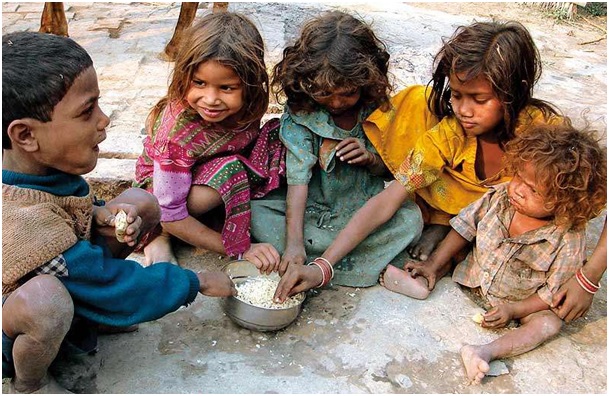

India has been placed at 103 out of 119 countries surveyed for the World Global Hunger Index (GHI) by two credible international NGOs based on the indicators of undernourishment and under-5 child wasting, child stunting and child mortality.

Its score is 31.1 in the GHI, among the worst in the world, and below close neighbours Bangladesh and Nepal in the SAARC region. The level of child wasting in India is at 21% – the highest for India.

According to FAO’s “State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World, 2018”, 196 million people are undernourished in India (14.8% of our population) and 51.4% of our women in the reproductive age are anemic. At least 20 crore Indians go to bed hungry daily.

These depressing figures must be placed against the reported growth of 4.5 times in the past 20 years of India’s GDP, the doubling of our foodgrains production and the tripling of our per capita consumption during that period.

There has also been the enactment of two highly-celebrated laws, the National Food Security Act (NFSA) of 2013 relating to food and nutrition security, and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) of 2005 for income guarantee from rural employment.

What can be done?

First should be the realisation that nutrition security is the bigger whole of which food security is a part. Along with this should be the realisation at the family level that food security is about stark hunger while nutrition security is about hidden hunger, and what this could imply in terms of child survival, gender dignity, health and education.

Second should be the realisation that however good is the macro-policy, poor implementation can nullify it.

We need laws that truly guarantee the marginalized people’s rights in full without rights-violating riders. An important strategy for providing, defending and expanding the rights of the poor in any law that claims to guarantee a particular right is to fine-tune it to the other related laws.

Has this happened in the case of the NFSA and the NREGA? Let us look at a few important instances.

The absolute need for nutritious “coarse” cereals as promised in the NFSA is beyond question.

These and minor millets are grown mostly in dry lands. However, the Government is in no position to offer these nutritious cereals in the Public Distribution System considering the inadequate area of coarse cereals under cultivation, levels of production and availability of surplus for procurement.

The main reason for this is the absence of a dry land agriculture policy that is specially supportive to these nutritious grains. This aspect is missing in this Act as well.

There is no specific mention of that in Schedule III, dealing with advancing food security. It is in these vast dry land tracts that India’s poverty and dismal

indices of human development, including hunger, reside. In this specific context, the Act fails to promote India’s food sovereignty, so essential for food security, by ensuring stable production and availability in these areas.

Also missing in this Act is a reference to an irrigation policy, based on a national water budget, that would prioritize irrigated dry (ID) nutritious crops (as against multiple irrigation wettings-dependent wet crops like rice). In fact, we need a shift in the cropping patterns even in the assured wet irrigation areas to ID cultivation.

This should also lead to the emergence of an autonomous public distribution system (PDS) based on community-led procurement and storage.

Such a system would not depend on grains moving across the country with all the accompanying evils of leakage and corruption, but would support nutritional needs of all sections of our people across the country, whether in the PDS or Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) or Mid Day Meal (MDM) or rural employment programmes.

It is that autonomy and sovereignty for producers and consumers together that we should aspire for in our search for food and nutrition security for India. There is no evidence of that in the NFSA 2013.

This lacuna is compounded by the omission in Schedule III of mention of promotion of Nutrition and Health Education for all, required to generate awareness of the link between health and what we eat.

The nutritional standards specified in the Act have been compromised by defining entitlement to mean ready to eat meals (a meal pre-cooked and heated before it is served), and including take home rations (THR).

It is well-established that nutrition interruptions for unconscionable periods occur in our Anganwadis because of use of ready to eat meals transported over hundreds of kilometers by contractors, as also delays, leakages and corruption.

Also known is that Take Home Rations are shared by the husbands and family members. Further, some of the “better off” pregnant women prefer not to eat at the Anganwadi Centre for “social” reasons but like to take the food home.

There is near unanimity amongst women that they would prefer locally cooked foods of varied recipes cooked at the Anganwadi centre and served hot, as also mandated by the Supreme Court.

The WHO says: “First three years are forever”. The cognitively all-important 0-3 cohort (the first 1,000 days of life) hardly figures in the Anganwadi centre. For that

to happen, the crying need is the conversion of the Anganwadi centres into full- time crèches. The key to the success of the ICDS programme is to enhance the attention of the system to the 0-3 cohort in terms of early childhood care and stimulation needs.

There can be no human resource development if this does not happen, as the window of opportunity for handling neurological development delays could close at 36 months, especially in the context of absence in rural India of technological advancements and facilities of latest neuroscience advancements.

The design of the Anganwadi services should be consistent with these needs of the below-3 year cohort.

Rural women labour do not feel confident about leaving their under-three children at the Anganwadi Centre as they are unsure that the care and security that such young children need would be provided at the centres, as presently staffed, trained or timed. Therefore, these mothers leave their very small children in the care of their older girl siblings, jeopardizing the latter’s right to education.

If not the mothers have to stay home foregoing their right to work. Many times, children above three are taken to the fields where the mothers work, depriving them of mental stimulation and Pre-school Education.

In order to safeguard the educational interests of older siblings, the livelihood interests of the bread winning mothers, the early childhood care and stimulation needs of the below-3 year old child, including the right of the child to be breastfed; and the pre-school needs of the children above 3 years – all rights under Article 21 of the Constitution – changes are required to extend the working hours of the Anganwadi Centre from 8:30 a.m. to 5 p.m. or as required to suit local conditions, so as to convert them into creches.

A crèche that provides services during the day for 8 to 9 hours, six days in a week, is what we need with expanded staff, infrastructure like sanitation, safe drinking water, kitchen garden, cooking space and provision of nutrition twice or thrice to the children. In short, to convert the Anganwadi centres in the ICDS programme into crèches (day care centres) is the reform required urgently.

This Act shows no awareness of the need for this reform in the ICDS programme.

As for the NREGA 2005, which is about the right to work for rural women, it has

also at a policy level singularly failed to promote the concept of a full-fledged crèche despite the huge resources it has.

The NREGA does not even mention the crèche, except in its operational guidelines where, in addition to the drinking water and first aid needs, a “shade for children” is mentioned, which can presumably be even that of a tree or a tarpaulin. The need for a crèche in the employment context is vital, as its absence is a serious violation of the Constitutional commitment made in Article 42 which stipulates just and humane conditions of work and maternity relief.

The final blow delivered to the entire concept of any kind of right to food and nutrition security comes at the very end of the NFSA in the concluding part of the Act.

Section 44 is a Force Majeure section which states that the Central Government or the State Government shall be liable for a claim by any person entitled under the Act “except in the case of war, flood, drought, fire, cyclone or earth quake affecting the regular supply of food grains or meals”.

This clause should altogether be dropped because, apart from hunger, these are the very raison detre for a food security law. War alone can, perhaps, be justified, but if it comes, the Indian people will be the first to understand. A force majeure clause of this kind ill-suits a rights-based law and needs to be summarily removed.

As for the NREGA, a disturbing feature in it in the context of the claim made to guaranteed employment is Section 7 (2) of the Act relating to unemployment allowance.

This section provides for such allowance at a rate that shall not be less than “one-fourth of the wage rate (fixed by the Act) for the first thirty days during the financial year and not less than one-half of the wage rate for the remaining period of the financial year.” If a Government fails to fulfill its promise of a certain wage rate, it should pay a higher rate to the deprived person including a penalty amount, and not a fraction to the promised wage.

Also objectionable is the rider in Section 7(2) that this payment is subject to the “economic capacity” of the State Government, in view of India’s vaunted economic growth. Long years ago the Supreme Court of India had also declared that the public policy in India is payment of a living wage to workers as stipulated in Article 43 of the Constitution and had also defined what constitutes a living wage.

Unfortunately, the NREGA did not provide for a nutrition component in its wage scheme.

These are some illustrations of what needs to be done in the context of the unflattering conclusions of the GHI 2018. What can and should be done is to review policies and laws that influence the outcomes like the GHI, and change them for the better through some suggestions of the kind made here.

India has a federal form of governance. Success of food and nutrition security measures call for negotiations vitally required between the Centre and the States pertaining to them.

Central institutions like the Reserve Bank of India and the Food Corporation of India and a number of state-level institutions would also be involved in these efforts. A massive programme of food and nutrition security calls for day-to-day interaction between all stakeholders, all key actors involved.

(K.R. Venugopal is a former Secretary to the Prime Minister of India and one of two first Special Rapporteurs appointed by India’s National Human Rights Commission (NHRC).

His commitment is towards all issues pertaining to Food and Nutrition security; and human rights enshrined in India’s Constitution and the International Human Rights Covenants, Declarations and Conventions. Venugopal’s unique experience and knowledge have been considered valuable in policy-related Governance.

Venugopal is the author of two books, “Deliverance from Hunger: The Public Distribution System in India” and “The Integrated Child Development Services A Flagship Adrift.)

Credits: https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-indias-hunger- index-what-can-be-done/326676